The story of Riociego is the same as that of other communities of the basin of the Salaquí River and all those of the Lower Atrato and Darién region in the extreme northwest of Colombia, closer to the Panamanian border than the center of the country where decisions are taken.

These are areas mainly populated by Afro-descendant settlers – the majority of whom arrived from various parts of the Chocó and Urabá since the 1930s and who, under Law 70, 1993, have garnered official legal recognition of collective ethnic territories where they co-exist with various indigenous groups.

The main reason for the area’s vulnerability is its location. It has been mentioned in several landmark legal decisions that have contributed to the safeguarding of its rights and have helped further claims that compensations are in order for the damages caused to it during the last four decades.

In 2013, when the Inter-American Court of Human Rights condemned the Colombian state for the deaths and displacement of thousands of inhabitants from 23 communities as a result of Operation Genesis, performed by the Colombian Army, it declared that “those communities are located in a region of great geostrategic importance in the armed conflict, particularly for armed groups operating outside the law, who have used this region as a corridor for the trafficking of weapons and narcotics, and have therefore pushed for the destruction of native species in order to plant coca, African palm and bananas.”

“…pushed for the destruction of native species in order to plant coca, African palm and bananas”.

CIDH

In September 2018, the Special Peace Jurisdiction prioritised the investigation of crimes committed by the FARC and the armed forces between 1986 and 2016 in the regions of Urabá (in Antioquia), the Darién rainforests and the Lower Atrato basin (both in Chocó) as one of its first cases. The conflict afflicted this region, “due to its geostrategic location and the potential of intercontinental and interoceanic connection infrastructure projects because of its access points and routes and closely associated road corridor,” explained the judicial branch of the new transitional justice system, which was established as a result of the landmark peace deal between the Colombian Government and the FARC in 2016.

Reality after the peace negotiations has followed a similar pattern: there are two new protagonists, with the same communities caught in the middle. In September 2015, at a time when FARC guerillas were preparing to lay down their weapons, a dissidence of the former AUC paramilitaries entered the region. They call themselves the Self-Defence Gaitanistas of Colombia (AGC) and the government dubbed them the Gulf Clan. Some months later, the guerilla of the National Liberation Army (ELN) took hold of other territories from the jungles around Baudó range to parts of the Pacific Coast above the Truandó River. The territorial struggle between both illegal actors has meant that it has been under fire for the last two years.

IN THE ATTRACT, THE RIVER SUBJECT TO RIGHTS CROSSING THE CHOCÓ FROM SOUTH TO NORTH, END WITH THE WATERS OF TENS OF RIVERS, BROKENS, AND DAMS THAT MAKE UP THE BASINS OF THE LOW ATTRACTION AND THE DARIÉN, WHERE DOZENS OF SURVIVING COMMUNITIES STILL SURROUND. GENERATED BY THE DISPUTE OF THE TERRITORY BETWEEN THE GROUPS ARMED BY THE NARCO-TRAFFIC AND WOOD-TRAFFIC BUSINESSES. PHOTOS BY: CARLOS ALBERTO GÓMEZ.

The Truandó River is the most strategic of all the tributaries of the Atrato River – the most important of the Colombian Pacific – because it is an easy exit point towards Panamá, the Pacific Ocean and the marshlands that interconnect the entire Lower Atrato basin with the Darién forests and Atrato River towards the Caribbean Sea.

Only humanitarian organizations have entered the area, and the community continues unaided. Over the last year, the Ombudsman’s Office has issued five early warnings, calling attention to the risk faced by the Afro-Colombian and indigenous populations in the Lower Atrato and the Darién region, but the situation grows increasingly more worrysome.

“There is no way even a piranha could get in here.”

“There is no way even a piranha could get in here.” This is how many locals describe the absence of national government, almost normalizing the dominance of the armed groups.

Civil servants of the Ombudsman’s Office calculated that their organization and the International Red Cross (CICR) have to help a family from Riosucio in a situation of forced displacement due to death threats every single week.

The Clearance of the Darién

Chocó, a humid and densely vegetated region which is even more biodiverse than the Amazon rainforest, has lost an average of 25,000hectares of forest over the last five years.

The warnings issued during 2018 by IDEAM, the national meteorological institute which monitors deforestation, indicate that the municipalities of Riosucio, Lower Baudó and Middle Baudó are home to the most advanced deforestation spots. In total there were warnings for 13 municipalities and 43% of the forest coverage loss was concentrated in the second trimester of the year – or rather, during this season, exactly one year ago.

Edersson Cabrera, coordinator of the forest monitoring group at IDEAM, declared that the main deforestation drivers in the entire Pacific Coast region have been illicit crops like coca and illegal gold mining, but that there were also worrying reports regarding logging -both legal and illegal – in the Lower Atrato.

In 2016 the global illegal wood trade was estimated to be worth up to one hundred billion dollars annually, and is responsible for 90% of deforestation worldwide, according to the International Union of Forest Research Organizations.

In Colombia, where the problem is acute, the Inter-institutional Committee for the Control of Fauna and Flora Trafficking implemented measures: from December 2018 it became necessary to processe a license for the gathering, transformation, transport or commercialization of any species.

Additionally, the Ministry of the Environment increased permit prices for the most vulnerable species of trees by four to five times, which is in effect a tax on the commercialization of wood.

These measures are intended to reduce the trade in rare endemic species, although not everyone is optimistic.

William Klinger, a forestry engineer, native of Chocó and director of the Institute of Environmental Investigations of the Pacific (IIAP), believes that these new measures will simply permit intermediaries to obtain more wood.

“The problem is that the new measures have no technical, practical bases”

William Klinger

“The problem is that the new measures have no technical, practical bases: you need to extract the capital that generates interest from the forest, and in this case it is growth. A forest grows around 20 cubic meters per year, and if it is not allowed to grow, the exhaustion of the forest is practically irreversible,” he explains.

The numbers of Colombia’s wood exports are not very clear. In reports by the International Organization of Tropical Woods, the country only appears as a documented exporter of teak, which is not considered a tropical wood. However, in analysis of the situation of different woods, made by the very same organization, Colombia appears as a producer of at least 2,100 cubic meters of tropical wood in 2016.

The same happens with national data. The Virtual Business Centre, which takes independent measures of international businesses, indicates that between 2017 and 2018, 28 kilos of wood left through the Caribbean port of Turbo, 1,382 of wood through Barranquilla, and 2,444 of tropical wood through Cartagena but the trade reports of the DANE (the national institute of statistics) registered zero exports in 2017 and 1,410 tons in the previous year.

“The heart of the deforestation problem is the lack of state control. We are a failed state in these border regions”

Manuel Rodríguez Becerra, Colombia’s first Environment Minister

For Manuel Rodríguez Becerra, who was Colombia’s first Environment Minister, the warnings in reality are useless. “They simply serve as the chronology of a tragedy,” he remarked.

“The heart of the deforestation problem is the lack of state control. We are a failed state in these border regions,” he added.

The Park Fires

In the first week of April of this year, in Los Katíos National Park, at the far northern end of the Lower Atrato, 1,800 hectares of forest burned. The only thing that managed to control the fire was a downpour, in an area that is protected due to its c condition as a natural a bridge for fauna and flora between Central and South America.

This means that many plants and almost all large mammals that make up our fauna and flora entered Colombia and thus South America through the Darién forest. And many continue to do so, like the jaguar, which moves from Central America to Argentina.

Two weeks earlier, another fire had destroyed 200 hectares of forest in the buffer zone around this national park of 72,000 hectares, which is connected to the Darién National Park of Panama of 550 thousand hectares and is also considered a UNESCO World Heritage Site due its biological diversity.

Thus, a new fire has been reported every week during this dry season.

This year’s events have led experts to recall the fires in 2016 which burned 10,000 hectares, eight thousand of which were forest, and affected the national park significantly. Over time, the authorities confirmed that these fires were caused by deliberate burning of land in order to extend agricultural use and by turtle hunting.

Thus, a new fire has been reported every week during this dry season.

It is also a stark reality that brings to mind the period of the early 1990s when the paramilitaries, under the helm of their bloodthirsty commander Carlos Castaño, cleared large swathes of jungle in order to open up land for cattle farming.

“The most likely theory is that this could be about large farmers who are taking advantage of the dry season to gain land for their ranches,” suggests Rodríguez Becerra.

The marshland

Indiscriminate logging directly affects bodies of water, mainly the marshes that act as regulators for water systems, because they absorb extra water when the river swells and release it when the river dries. This destabilizing of the marshland circuit may be the cause of the many floods that have plighted Chocó in recent years.

IN THE LOW ATTRACT AND DARIÉ, THE INDISCRIMINATED FALLING OF TREES IS A LEGACY OF WOOD COMPANIES OF THE 1950S. FOR SURVIVAL FOR NATIVES OR FOR BUSINESS FOR TRAFFICKERS, THOUSANDS OF LEAVING TREES ARE LEAVING MORE VALUES. WITH IMMINENT DANGERS FOR ITS PROXIMITY TO THE LOS KATÍOS NATIONAL NATURAL PARK AND THE DARIÉN PLUG. PHOTOS BY: CARLOS ALBERTO GÓMEZ.

In 2014, the group of oceanic studies at the University of Antioquia conducted a study of water quality in the wetlands of the Atrato River floodplain. In 18 of the bogs studied they detected a low animal presence, an alarming finding considering that the wetlands act as a type of nursery for fish in the region, just as the mangroves do. The fish pass through there, grow, fatten and later head to the rivers, which is where fish stocks occur.

This is why, Klinger explains, species such as manatees, river otters, and the variety of catfish locals call maidens have gradually disappeared.

Some signs allow room for hope, such as the reappearance of a fish species called widemouth or cachana (Cynopotamus atratoensis), which researches considered extinct ten years ago. After published “wanted” posters all over the Chocó, this encouraging news arrived a year and a half ago.

“The first task we have is rescuing the wetlands so that the water surface increases, and the second one is controlling forestry activities and cattle farming,”

William Klinger

“Is it reversible? I believe so, but at a price. The first task we have is rescuing the wetlands so that the water surface increases, and the second one is controlling forestry activities and cattle farming,” Klinger says.

Former minister Rodriguez Becerra was one of the pioneers behind the Great Alliance Against Deforestation that brought together diverse actors from civil society to create pressure on the government to act. He proposed to select three or four hotspots that have difficult security conditions and critical risks of deforestation, in order to reestablish state control in them and provide public services such as health, education and employment to these communities as a way to halt forest clearances. “It is complicated, but it is also feasible,” says Rodríguez Becerra.

El motor

SOURCE: UNITED NATIONS OFFICE FOR DRUGS AND CRIME, UNODC

“Coca is the fuel that drives further interventions, both for cattle-farming and for deforestation,” says Edersson Cabrera of IDEAM.

This fuel has already arrived in Lower Atrato and it is getting close to the Darién. Up until 2017 only a few plot holders had small coca crops, what they would call a quart. But then it arrived on a larger scale. It arrived in Truandó in March, when armed groups authorized the planting of coca, and by the end of the year it had spread to all the communities in the area.

“They bring us the seeds, the give us a plant, guarantee us a sale, but the truth is that we sell our souls to the devil,” reports a farmer who has half a hectare of coca in his farm, and who asked for his name not to be used due to the associated safety risks of talking about this issue.

“They bring us the seeds, the give us a plant, guarantee us a sale, but the truth is that we sell our souls to the devil”

Although there are no reports for 2018 yet, the latest census by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) revealed that Chocó had, by late 2017, 2,611 hectares planted with coca, a figure which only represents about 5% of the planted area in Nariño (the main coca growing department of the country), but it meant an alarming 44% increase from 2016. The following statistics show how cultivation of this plant is increasing rapidly:

Calculations by human rights organizations working in the area indicate that 80% of the population has already planted coca to some extent, the majority under duress.

The road in the middle of the jungle

A yellow line, of a lighter hue than a river, caught the attention of the analysts of the Forests and Carbon Monitoring System at the IDEAM.

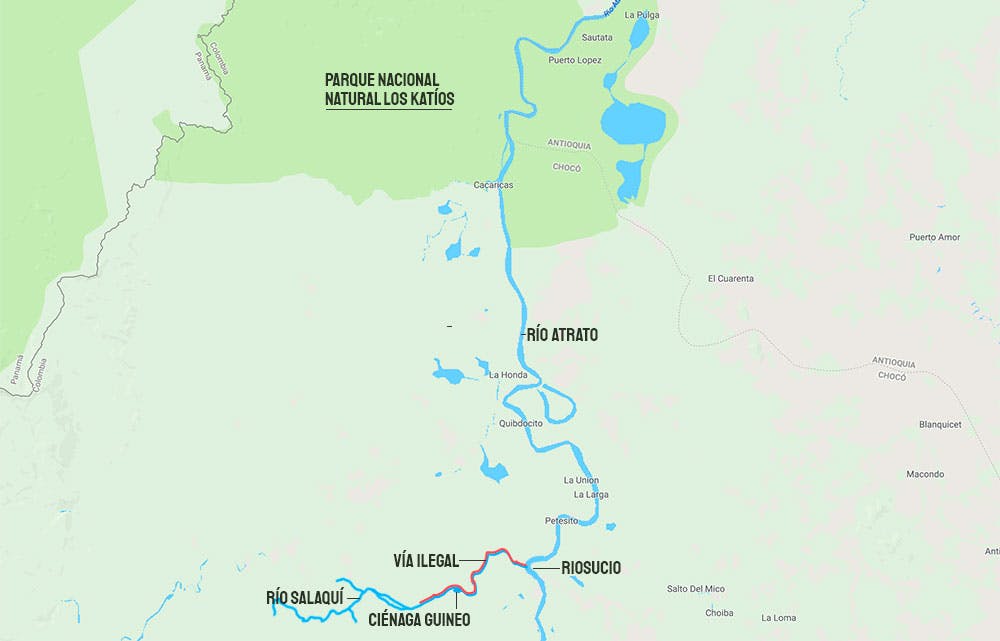

While processing satellite images from PlanetLabs, they identified the line and were able to convert its coordinates and monitor it over the course of several weeks. Their diagnosis: there was already an illegal road adjacent to the Salaquí River on the western edge of the Atrato River and entering into the dense thicket of forest.

Between November 1st, 2018 and the January 2nd this year, the road grew by 14 kilometers, which is the equivalent of one kilometer of construction every four days. If it continues at this rate, it will be a 90-kilometer road by the end of the year.

Between November 1st, 2018 and the January 2nd this year, the road grew by 14 kilometers

There was immediate alarm because it seems the same modus operandi as seen with the construction of the Jungle Marginal road project two years afo. This was a long-planned and awaited road that the government wished to construct to link the Amazonian departments of Guaviare and Caquetá, which illegal groups anticipated and began opening in the middle of the Amazon Jungle. It now runs dangerously close to the Chiribiquete Range National Park, one of Colombia’s most important natural treasures and recently declared a World Heritage Site for its biodiversity.

The area of Riosucio where the road passes is jungle, and although it is not a natural reserve nor does it fall in the buffer zone of a national park, it is most likely that an environmental authority would block permission for this type of construction here.

if it was to follow the routes that are currently used by people and drug traffickers, it could mean the definitive opening of a rainforest so dense it is colloquially known as the Darién Plug.

Analysts’ calculations suggest this could be a road that is up to three to four metres wide, enough to allow a 4×4 vehicle to pass, and if it was to follow the routes that are currently used by people and drug traffickers, it could mean the definitive opening of a rainforest so dense it is colloquially known as the Darién Plug.

Although it has since been shelved, the project to build a road that would connect Central and South America was named decades ago as the Pan-American Highway, and included a 62-kilometer stretch which did not directly touch Los Katíos National Park, but which –according to its management guidelines- “did include works in its surrounding areas which would have generated pressure on the neighboring territories of the protected area.”

“This track, just like any other legal or illegal path, brings settlers and that generates deforestation”

Manuel Rodríguez Becerra

The problem is that the Darién rainforest is biologically very diverse and also very fragile. “This track, just like any other legal or illegal path, brings settlers and that generates deforestation,” says former minister Manuel Rodriguez Becerra, adding that the only thing that has saved the area thus far is that Panama has no interest in building the road.

Studies done by the IDEAM seem to support what he says: 72% of the deforestation in Colombia is located less than eight kilometers away from roads.

The process of illegal road construction has accelerated in the country, stemming from “the occupation of spaces abandoned by the FARC which have resulted in projects for transporting weapons, troops, migrants, coca, wood, gold and any other commodity,” according to Rodrigo Botero, director of the Foundation for Conservation and Sustainable Development (FCDS), who has been monitoring the situation in the Amazon.

The consequences for biodiversity, local communities, and collective heritage in general are enormous, explains Botero, because, “these corridors of movement installed today are often done by force, sometimes with a political aim, and sometimes simply paid for by outside actors.”

The possibility of the opening of the Darién Plug would probably mean an irreparable loss as it would severe the biological connectivity of Mesoamerica

In the case of the road in Salaquí, it is not a small threat. The possibility of the opening of the Darién Plug would probably mean an irreparable loss as it would severe the biological connectivity of Mesoamerica, which would be as serious losing the connectivity between the Andes and the Amazon.

“This is your classic tragedy that happens in the tropical world, because a road appears and then the most basic and crude exploitation follows, which is extracting meat and wood,” says Esteban Payán, Ph.D. in biology and South American director the Panthera Foundation, which oversees conservation of the jaguar corridor on the continent.

“You are no longer just a hunter once you have a gun. You can kill a tapir, carry it on your back. And once you get a motorbike or a van, you can take 20 tapirs, and have a fridge that preserves the meat, get a chainsaw, build a camp and kill a ton of them, have a mountain of meat that doesn´t rot, and go back and do it again,” he explains.

This entire situation, experts argue, causes the fragmentation of ecosystems. It means there´s no open space whereby the animals can move freely across the land, see barriers installed in their way, causing animal populations to become separated from each other.

“Animals are not willing to cross a road simply because it is open space. For example, an agouti or a lowland paca will not expose itself to the danger of walking for five meters in the open because a jaguar could catch them. Sloths, for example, lose the ability to reproduce because they are not going to look for females on the other side of the road,” explains Payán.

In the long term, this creates genetic segregation on both sides.

Jaguars, the main research subject for Payán, would be the first to disappear because of hunting spurred by fear or because they feed off other animals. But there are also other species like butterflies that are particularly sensitive to changes in their environment and could soon go extinct in the area.

This also affects Los Katíos National Park because the protected area could lose its effective conservation status, which it only maintains due to its buffer zone where the animals don´t come into contact with the outside world.

Another threat which has been seldom analyzed are coyotes. This controlled mammal in USA has never been able to cross over to South America because they are not jungle animals, but they are only 20 kilometers away from the Darién Plug.

They could become a plague, explains Payán. “The moment that a path opens up, they are going to come and there will be a biological invasion of coyotes that will completely change the dynamic of fauna of South America, because this is a very adaptable animal that moves by day and by night. It is what we call a generalist animal. By this I mean that it eats whatever, so it will come and eat everything in its sight,” he adds.

“There is a domino effect of ecological impacts”

Esteban Payán

Also, according to Rodrigo Botero, there is an ever increasing fragmentation of key ecosystems and forest areas in indigenous reservations, Afro-Colombian communities, forest reservations and national parks, most of which is associated with illegal activities which in its turn multiply the environmental and social impact on these particularly vulnerable populations.

Wherever these roads coincide with international borders or large wooded areas, they generally attract the development of illegal activity, and this the main fear vis-à-vis the Salaquí road. A security analyst who investigates matters of narco-trafficking, but who asked that his name be omitted for security reasons, expressed fears that this road could mean the beginning of a circle of cocaine production and export in the area.

The current routes used are not especially profitable as they have dangerous parts which can delay deliveries by up to a week, or they are simply inaccessible.

The current routes used are not especially profitable as they have dangerous parts which can delay deliveries by up to a week, or they are simply inaccessible. Therefore, drugs arrive in the vicinity of Bahía Solano on the Pacific Coast, from where they are then exported.

This hypothesis makes sense when verifying the increase in illicit crops which give way to cocaine production, and which require access between laboratories and embarking points where the drugs leave the country. Intelligence organizations have information on the increase in the amounts of cocaine exported from the Gulf of Urabá in the Caribbean given the arrival of Mexican cartels in southern Colombia.

“What could be going on is that they are implementing their business model: you grow the crops, we operate laboratories, process the leaves and meanwhile we work on the road in order to have a swift route to get the drugs out,” says the analyst.

Besides the disastrous effects that this illegal tarde would have on the vital ecosystems of the Lower Atrato and the Darién are the consequences for the local population

Besides the disastrous effects that this illegal tarde would have on the vital ecosystems of the Lower Atrato and the Darién are the consequences for the local population, who have been victims of the economic interests of various illegal actors for the last forty years.