Taking care of a national park in Colombia, with its long-standing armed conflict, is a risky and unappreciated job. After years of oblivion, the families of three murdered park rangers could finally understand what happened to their loved ones now that their cases could reach the transitional justice system created by the 2016 peace agreement signed by the Colombian government and the Marxist FARC rebels.

Wilton Orrego was patrolling a forest in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta National Park on January 14, 2019, when he was intercepted by unknown individuals and shot five times.

Orrego, 38 years old, died hours later in a hospital in Santa Marta. He left behind his wife and a teenage daughter, along with two years of work as a park ranger in a corner of the Colombian Caribbean where beautiful beaches, bird watchers, and tourists live side by side with criminal groups vying to transport drugs out of the country. His murder highlighted an almost invisible risk in Colombia: caring for the jungles, rivers, high-mountain paramos and the natural wealth of the second most biodiverse country in the world.

caring for the jungles, rivers, high-mountain paramos and the natural wealth of the second most biodiverse country in the world.

Over the past 25 years, at least 11 national park rangers have died in violent circumstances while safekeeping the natural areas under their care, powerless against the financial interests of multi-million dollar businesses such as drug trafficking, illegal mining, and war.

Even though they were dedicated state employees convinced of the value of their mission, the cases of Martín Duarte of La Macarena Range National Park, Jairo Varela of Paramillo National Park, and Jaime Girón of Churumbelos Range National Park sadly show a similar pattern: their cases have remained in absolute impunity, their families feel abandoned by a forgetful State and their colleagues continue to work in equally precarious conditions.

their cases have remained in absolute impunity, their families feel abandoned by a forgetful State and their colleagues continue to work in equally precarious conditions

However, the signing of a peace agreement with the former Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) in 2016 has opened a window of opportunity to understand what happened to them.

A group of respected environmental scientists and leaders has been working since last year on a proposal for the new transitional justice to investigate the ways in which the environment and its caretakers have been affected by violence, as part of its core mission to investigate and judge the crimes that took place in the context of the Colombian armed conflict.

In two of the three cases, those of Martín and Jairo, there is strong evidence that FARC guerrilla members who laid down their weapons two years ago and are in the process of reintegration into civilian life are accountable for their deaths. The FARC could therefore, as part of their commitment to peace, help these families understand what happened and ask them for forgiveness.

The guardian of La Macarena

Martín Duarte was so satisfied with his job as a park ranger that he decided to study an undergraduate degree to become an even better civil servant.

The mission of this 36-year-old agricultural technician from Bogotá was to safe keep La Macarena Range National Park, a rocky oasis in the middle of the lowlands where the Colombian Amazon begins, slightly detached from the Guiana Shield. Although Caño Cristales, also known as the “seven-colored creek,” is an iconic destination whose pictures adorn tourist brochures and airport posters throughout the country, only until recently have Colombians begun to travel to this remote mountain range thanks to improved security conditions.

only until recently have Colombians begun to travel to this remote mountain range thanks to improved security conditions.

In 2008 La Macarena was still the setting of intense confrontations between the military, guerrillas, and other paramilitary groups. In fact, it was the epicenter of one of the main political and military strategies -dubbed “territorial consolidation” – with which the Colombian government managed to reverse the correlation of forces with FARC, pushing the Marxist rebel group towards a negotiation table.

At that time, as is the case today, one of the primary functions of park rangers was to work with local communities in and around the parks. Martín’s passion for this work motivated him to enroll in a community social psychology. Every week he rode his motorcycle for an hour from his cabin in San Juan de Arama to the National University of Distance Education (UNAD) in the town of Acacías, both in the department of Meta. After eight semesters, he only needed to study more six months for graduation.

Duarte had been working in Colombia’s National Parks system for 13 years. His work had begun in the national park adjacent to Bogotá that protects the Sumapaz paramo (moorland) at the top of the mountain range. From there he moved to Los Picachos, which safeguards the transitional forests that connect the Andes and the jungle. He finally arrived in La Macarena after separating from his wife and requesting a transfer to be closer to his daughter Stephanía.

The circumstances of Martín’s death are still confusing. What his family has been able to reconstruct is that while returning to his cabin after working with local peasants, he probably came across a group of armed men he did not know. There were four of them, and they were carrying a woman by force.

while returning to his cabin after working with local peasants, he probably came across a group of armed men he did not know.

After that, Martín spent two days in Bogotá on leave. He returned early on Friday to the national park, not having told anyone about the scene he had witnessed, undoubtedly aware that it could cost him his life.

On Saturday, February 2, 2008, at about 8:30 p.m., Martín called his aunt, Carmen Elena Triana, whom he frequently visited in the nearby town of Granada. “Elenita, I am hurt,” he blurted. “Come pick me up,” he told her in an urgent, intermittent voice. He did not answer his phone again. Although the circumstances around his death are still uncertain, evidence suggests that the same people he had seen had gone to look for him and shot him in the back while he was working.

“He didn’t receive a warning. They did not give him a chance. They shot him in the back”

Elsa Acero

When local authorities reached the cabin, Martín was already dead. The medical diagnosis was hypovolemic shock, caused by a gunshot wound to the spinal cord, severe blood loss, and failure to receive medical attention.

“He didn’t receive a warning. They did not give him a chance. They shot him in the back,” said his mother, Elsa Acero.

A month later, a military operation led by the Gaula, an anti-kidnapping unit of the Colombian Armed Forces, was able to rescue 22-year-old Libia Camila Domínguez. The kidnappers were demanding a one-billion-peso ransom (around US $500,000). Four men were captured, along with a small arsenal: an AK-47 rifle, a submachine gun, two grenades, two shotguns, and two revolvers.

The four men were convicted of extortion and aggravated kidnapping with sentences of up to 59 years: Carlos Adolfo Plazas Ramírez, also known as “Parrilla”, a salesman; Elisein Pinto Pérez, “Pedro”, a construction worker; Uriel Beltrán Lozano, “Fredy”, salesman; and Gonzalo Chávez Vargas, “Andrés”, driver.

one day after hearing a gunshot in the forest, one of the men told her they had had a problem with a “loud-mouthed” environmental engineer

The trial for Martín’s murder was so traumatic for the Duarte family that they stopped attending the hearings, afflicted by the constant procedural postponements. For them, the case looked solid and clear: Libia Camila testified from behind a one-way mirror that prevented her former captors to see her that one day after hearing a gunshot in the forest, one of the men told her they had had a problem with a “loud-mouthed” environmental engineer. “You know they’re looking for you and this man seems to have seen something, so he was shot”, she recalled one of her captors telling her.

“So much red tape, but no results”

José Venancio Duarte

On April 28, 2014, six years after Martín’s assassination and despite a request from the Attorney General’s Office to convict all four suspects for aggravated homicide, a Bogotá court acquitted them due to an absence of compelling evidence. “It is not possible to conclude that there is direct and serious evidence that can distort the presumption of innocence of the accused,” Judge Martha Cecilia Artunduaga determined.

“So much red tape, but no results,” said Martín’s father, José Venancio Duarte, somber but without a trace of bitterness.

Rangers in the middle of war zones

Being a park ranger in Colombia means much more than taking care of a national park. In a country ravaged by a 50-year-long war that left 220,000 dead and 8.8 million victims, it means having to deal with countless armed groups, often in open confrontation between each other, and to persuade these groups that park rangers’ are not a threat to them.

Even today park rangers must deal with a number of very complex problems: with vast illegal coca and opium poppy crops, with dredges and backhoes thirsty for hidden gold and coltan, with rampant deforestation deliberately seeking to “clear” the forest to sell precious wood or to ensure the illegal appropriation of public lands, or with anti-personnel mines planted to obliterate the legs of any human or animal who steps on them.

Martín was not the first, nor the last. The list of fallen park rangers is long and covers almost the entire geography of the country.

Three years later, two other park rangers died in violent circumstances.

On April 29, 2011, environmental technician Jaime Girón Portilla was walking on a trail in the Churumbelos Range National Park, which shelters 970 square kilometers of rainforest in southwestern Colombia, when an anti-personnel mine fatally wounded him in his leg. He was evacuated in a military helicopter, but died before reaching the hospital in Villagarzón (Putumayo).

“He always had the goal of working in National Parks. He studied the names of all the birds in his booklets and was always alert to damage in the forests. ‘Environmental impact’ were the words we heard him mention the most”

Yadira Vargas

Girón, who had barely been on the job for four months, was in the middle of a week-long tour to help a neighbor georeference a piece of land that would be destined for conservation. “He always had the goal of working in National Parks. He studied the names of all the birds in his booklets and was always alert to damage in the forests. ‘Environmental impact’ were the words we heard him mention the most,” recalled his wife Yadira Vargas, for whom the accident meant being forced to raise two young children on her own.

Five months later, Jairo Antonio Varela was murdered in Paramillo National Park, on a highly coveted drug trafficking route used to move drugs to the Caribbean Sea.

armed men had intercepted them on several occasions to ask why the land was being measured without permission.

Varela, age 48, was not only a park ranger, but also the recognized leader of Saiza, a community displaced by paramilitaries who had recently returned to their homeland. Verdad Abierta, a respected news outlet specializing in documenting the armed conflict, reconstructed the story of what had happened: Jairo and his colleagues had been updating the census of 1,039 families living within park boundaries in order to compensate them for those activities they could no longer carry out given that they lived inside a protected area. To do so, they visited the 33 rural hamlets in Jairo’s birthplace, talking to their inhabitants and writing down what each family did on their farm.

The census takers soon ran into a problem: in a third of the villages, outsiders were planting coca crops. This was the result of a repopulation effort seemingly led by the FARC. Although Jairo had spoken to a local guerrilla leader and had informed him of the importance of the census, armed men had intercepted them on several occasions to ask why the land was being measured without permission.

All three park rangers were the eyes and ears of the Colombian State in territories where it has historically been absent and rife with much more powerful vested interests beyond their control.

On the night of October 5, 2011, he was summoned by them to a meeting from which he never returned.

All three park rangers were the eyes and ears of the Colombian State in territories where it has historically been absent and rife with much more powerful vested interests beyond their control.

“The burden of being perceived as the State is highly unfair. We assigned park rangers surveillance and control tasks to deal with problems such as hunting, mismanaged tourism, or misuse of water as if we were in Yellowstone. It was never thought that armed with a uniform and a code of natural resources they would have to face guerrillas, paramilitaries, and criminal groups,” said environmental lawyer Eugenia Ponce de León, former director of the Humboldt Institute and former environmental deputy at the State Ombudman’s Office.

“It was never thought that armed with a uniform and a code of natural resources they would have to face guerrillas, paramilitaries, and criminal groups”

Eugenia Ponce de León

As Martín’s mother said, “They did not have as much as a pin to defend themselves, the branches of trees perhaps. They were totally unprotected.”

The window of opportunity to find out what happened

The families of these park rangers have one thing in common: above all, they want to know exactly why they died.

“We really want to know what happened. Had he not made that call, bravely and fatally wounded, we would have no idea about what happened. We would still be looking for a missing person,” said Javier Duarte, Martín’s older brother.

“We really want to know what happened”

Javier Duarte

Like many victims of the conflict, their families want to know the truth of what happened more than anything else. If one took the 27,000 proposals sent by victims to the peace negotiators in Havana as a reference, those who suffered most from violence wish to have the possibility of rebuilding their lives (34%) and having truth (16%), more than seeing justice (11%).

The Duarte family have heard several hypotheses about who Martín’s murderers were, but few certainties. One possibility mentioned was that in the La Macarena area, two of the acquitted detainees were FARC guerrilla members and the other two were civilians in cahoots with them. Another possibility was that the kidnappers were new guerrillas in the area, which would explain why Duarte’s identity was unknown to them.

Eleven years after Martín’s murder and two years after the peace accord that ensured 13,049 members of the FARC abandoned their weapons, new clues finally emerged.

After comparing the names of the four men convicted for Libia Camila’s kidnapping with the official lists of demobilized FARC members, we found that two of them do have connections with the former Marxist guerrilla group.

most persons do not enter the Colombian prison system due to their condition as rebels but rather for specific crimes they committed.

Elisein Pinto appears as one the 3,170 “persons deprived of liberty” (in the jargon of the peace agreement) that FARC recognized in the lists of combatants they submitted. After due verifications, the Government accredited him as a member of FARC, a step that makes him a party to both the obligations and benefits of the deal.

Although a decade has passed since his conviction, his membership was only established with certainty until now, given that most persons do not enter the Colombian prison system due to their condition as rebels but rather for specific crimes they committed. This is the reason why the state often did not know which convicted prisoners were FARC members.

Carlos Adolfo Plazas’s case is more complicated. His name appears on the same lists, but was later excluded on September 22, 2017 at the request of the FARC, thanks to a provision that assigned them the responsibility of drafting these lists.

All of this means that at least one of the suspects of Martín’s murder could help reconstruct the events that happened on February 2, 2008.

This scenario is possible because the Colombian peace deal devised an innovative transitional justice system in which, instead of privileging some victims’ rights over others, Colombia chose to try to satisfy all of them.

at least one of the suspects of Martín’s murder could help reconstruct the events that happened on February 2, 2008.

Thanks to this formula, FARC former combatants may receive more lenient sentences for serious and representative crimes, such as murder and kidnapping, if –and only if- they meet three conditions: acknowledging their responsibility, telling the truth, and personally helping redress victims. With this model, Colombia seeks to fulfill its legal obligations as well as guaranteeing victims’ right to truth, justice, reparation, and non-recurrence.

In 2018, three institutions began working as part of this transitional justice system. The Special Peace Jurisdiction (or JEP) is in charge of investigating, prosecuting, and sanctioning the most serious crimes, while the Truth Commission is reconstructing what happened during conflict. Finally, the Disappeared Persons Search Unit is searching for approximately 45,000 missing persons, including park ranger Daniel Moyá who disappeared in Los Katíos National Park.

The creation of this transitional justice system, which will only work between three and 15 years, led several scientists in the environmental sector to ponder: What if the Special Peace Jurisdiction and the Truth Commission investigate the environmental damages caused by conflict, from attacks on pipelines to the murder of park rangers?

“Next to the horror of what happened during war, this seems like a minor issue but it isn’t. Our national parks have been mined, bombed, cultivated with coca, sprayed with glyphosate [to eradicate coca] polluted by mercury and oil spills, and have seen roads opened and their animals eaten,” said Eugenia Ponce de León, who has worked with park rangers since she began her career three decades ago as a National Parks attorney.

“Our national parks have been mined, bombed, cultivated with coca, sprayed with glyphosate [to eradicate coca] polluted by mercury and oil spills, and have seen roads opened and their animals eaten”

Eugenia Ponce de León

She and other environmental lawyers drafted a legal analysis proposing that there is a unique opportunity today to measure the environmental cost of violence in the national parks. They are now persuading National Parks to formally propose the transitional justice system to open such a case.

One of their chief arguments is that the Rome Statute, which created the International Criminal Court and to which Colombia is a party, states that attacks which cause “extensive, lasting, and serious damage to the natural environment” could be considered war crimes.

“National parks have not only been the epicenter of war, but also harbor strategic resources: minerals, energy, an agro-industrial potential, and infrastructure possibilities. Despite the peace agreement, this collective heritage of all Colombians is once again in a position of suffering victimization, because those interests and those resources are still there,” said Rodrigo Botero, director of the Foundation for Conservation and Sustainable Development (FCDS), who was the head of the regional office of National Parks in the Amazon for ten years.

“Despite the peace agreement, this collective heritage of all Colombians is once again in a position of suffering victimization, because those interests and those resources are still there”.

Rodrigo Botero

They did not come up with this idea out of nowhere. The peace agreement mentions the possibility of reforestation being considered as a form of reparation to victims and a job opportunity for former combatants returning to civilian life. In addition, coca substitution programs include a plan to eradicate the 8,301 hectares of coca currently planted within 16 parks, including 2,832 hectares in La Macarena. Finally, the Truth Commission’s mandate included the need to clarify the impact that the conflict has had on Colombians’ constitutional right to a healthy environment.

These ideas, however, will need political momentum since recently elected President Ivan Duque promised to implement the peace deal but seems more inclined to dilute its historical importance. This uncertainty grew in March, when President Duque announced his decision to object several parts of a law that regulates the work of the peace tribunal.

“This is a long-standing debt in Colombia. We must accept the environmental costs that war left us. We have an opportunity to render them visible and see exemplary rulings can help us ensure these episodes never happen again,” said Ponce de León.

“We have an opportunity to render them visible and see exemplary rulings can help us ensure these episodes never happen again”

If the idea gains traction and the special tribunal decides to open an environmental inquiry, Colombia could better understand the contradictory role played by guerrillas. For example, FARC used to hide in the dense green carpet of the jungle and imposed environmental bans on hunting or logging, while at the same time blowing up oil pipelines and financing itself through criminal and predatory economies like coca crops and illegal mining.

The direct responsibility of the FARC is evident in at least another of these three cases. “Unfortunately, yes, that decision was made,” recognized the commander of the 58th Front of FARC, who went by the name “Manteco,” when Verdad Abierta asked him about the death of Jairo Varela in 2016.

“Jairo had been told 15 days before his death to stop what he was doing: he said the census and his land measurements would help people legally, but he was being deceptive. What he was doing was help Parques negotiate with locals and ultimately displace them,” he added on camera, in an investigation on the Paramillo Massif.

A year after that admission, Manteco, or Yoverman Sánchez Arroyave, handed over his weapons as part of the peace agreement and settled in the Gallo concentration zone in Córdoba to begin his reintegration process. After many logistical difficulties in this remote camp, his group of former FARC combatants moved to another camp in Mutatá (Antioquia) where they began their new life and where Sánchez remains today.

In the case of Jaime Girón, direct responsibility is more difficult to establish, since both FARC and the National Liberation Army (ELN) guerrilla -which remains active- have used landmines as a weapon of war and were present in the area.

In any case, landmine use -which has left 11,462 victims in Colombia- is one of the crimes the now-demobilized FARC will have to acknowledge in the transitional justice system. FARC was described as “the most prolific mine users among the world’s rebel groups” by the International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL), which measures each country’s compliance with the Ottawa Convention to clear these explosive devices.

If the environmental dossier reaches the special tribunal and the Truth Commission, many former FARC members, including Elisein Pinto and Yoverman Sánchez, have a legal duty to tell the truth about cases like Martín and Jairo’s.

Civil servants of an insensitive state

Many families are feel hurt by the state their loved ones worked for, which they perceive as distant and indolent with their tragedies.

“There were no phone calls, they did not come to visit us. Do you think they know what happened to his 13-year-old daughter? Did it ever occur to them to provide a psychologist for Martín’s mother, his father, his siblings? There has been a complete absence of the state,” said Elsa Acero, sitting in the living room of her home in western Bogotá.

“There were no phone calls, they did not come to visit us. Do you think they know what happened to his 13-year-old daughter? Did it ever occur to them to provide a psychologist for Martín’s mother, his father, his siblings? There has been a complete absence of the state”

Elsa Acero

On the table in front of her lies a photo of Martín, smiling and wearing his blue ranger’s vest while riding a boat in Amacayacu National Park. “He did not deserve that because he devoted his whole life to national parks. He was in love with his job,” she added.

“There was never any indifference. Even though many families live in remote places, we have gone out of our way to provide them as comprehensive an assistance as we can. We try to give it to our employees and contractors: we already have many cases among them, including persons who have been threatened,” said Julia Miranda, who has been director of National Parks for 15 years.

In response to a freedom of information request we submitted, National Parks explained that it did intend to provide psychosocial assistance to relatives of murdered park rangers, but that “due to budgetary and logistical constraints, the insufficiency of the staff to address such issues at the time and the difficult conditions of the areas at the time of the events, it was only possible to have a few initial contacts with them”.

“due to budgetary and logistical constraints, the insufficiency of the staff to address such issues at the time and the difficult conditions of the areas at the time of the events, it was only possible to have a few initial contacts with them”.

Over time, many of Martín’s objects have been lost. His notebooks and psychology books were given to a niece. His “tree lamp”, made in his free time from a tree stump, was thrown out because it took up much space. Only a poster of a Victoria regia lotus and a handcrafted maraca made from a gourd survive.

The Duartes feel they have had to go through too many things on their own, from coping with the pain of losing a child to raising their granddaughter Stephanía. Now they are happier because she graduated as a civil engineer from La Salle University, became an infrastructure expert and just entered the Naval Cadet School to pursue a career in the Colombian Navy. Following her father’s footsteps, she worked for six months in the mayor’s office of Puerto Nariño, in the Amazon.

They underscore how the only financial support they received came from the Thin Green Line Foundation, founded by Australian Sean Willmore to support the families of fellow park rangers who have died in the line of duty around the world.

“I am a civil servant and I every time I remember that my brother lost his life for a institution, I realize it is not worthwhile. Public officials have a problem: we give so much for so little,” said Javier Duarte.

“Public officials have a problem: we give so much for so little”

Javier Duarte

It was not just the state who left them high and dry. A huge file shows how Colmena, the labor risk insurance company, denied the Duarte family the financial compensation they were entitled to for Martín’s death in the line of duty.

After extensive correspondence between National Parks and a professional risk lawyer from Colmena, the company notified the Government on April 4, 2008 that, in its own words, “what happened is not clear” and that the events “are not related to professional risk factors related to the professional functions performed by Mr. Duarte as a technologist.” Therefore, it determined that “the presumption that an ordinary motivation may have caused the event has not been disproven, which is why Colmena Riesgos Profesionales categorizes the event as of ordinary motivation and not professionally-related”. The Duartes were not even notified personally of his death.

The Colombian Government ratified the Duarte’s version of the events. “All the pertinent administrative steps were taken by the Administration in its claim, without obtaining a positive claim result,” National Parks acknowledged, pointing out that the insurance company argued that Duarte had not alerted his boss that he would be in the park and that he had asked for a day off for personal issues.

“All the evidence was available; their itinerary was well documented. Everyone made sure they were not liable”

Yadira Vargas

A similar story happened to Yadira Vargas. Although she did not keep any of the correspondence, she assures that the state-owned insurance company, Positiva, did not recognize Jaime’s accident either.

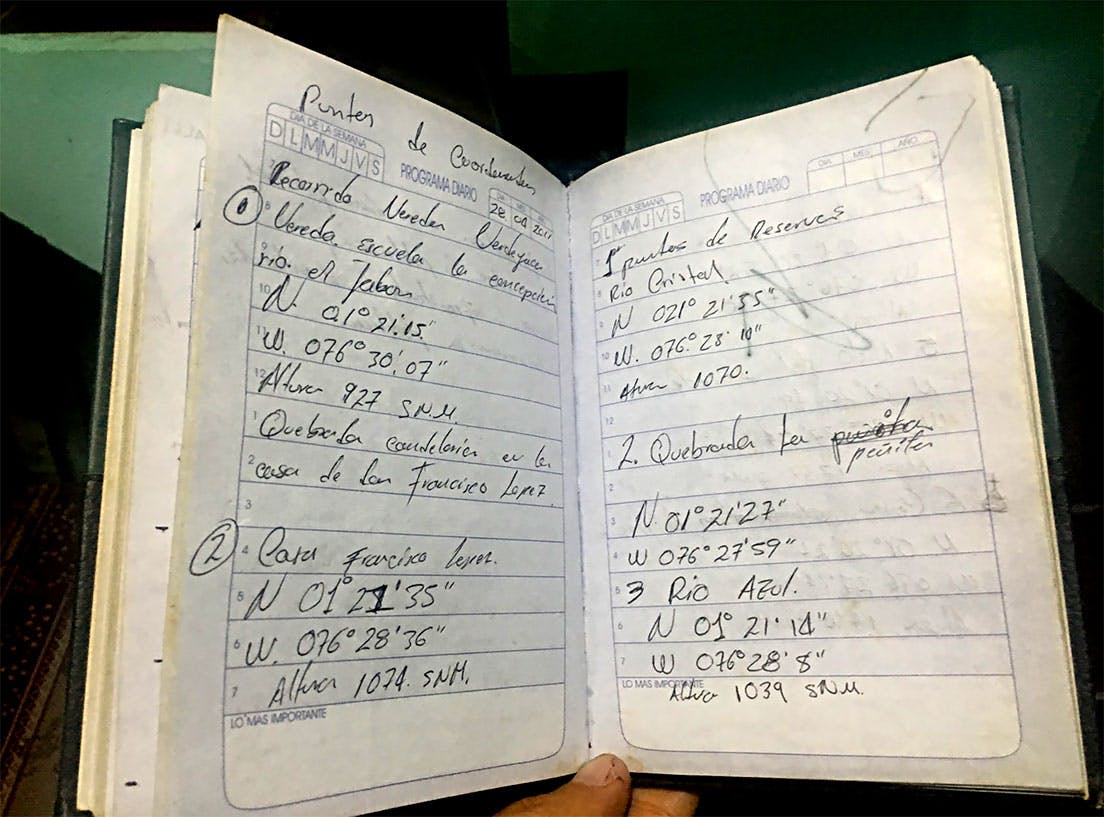

“All the evidence was available; their itinerary was well documented. Everyone made sure they were not liable,” said Yadira, who still treasures her husband’s blue field notebook at home. In its pages Jaime meticulously wrote down the coordinates, heights, and names of each place that was going through that fateful week, along with the dates of the day he met his wife and the birthdays of their children. On Friday, the fifth day of his tour, the logbook was left blank.

“Money is not going to bring him back, but I went through so much raising two small children on my own, one of them only a year old,” said Vargas, who was fired from her job at a healthcare company two months after losing her husband because –they argued- she wasn’t able to separate personal issues from her work. To provide for Lesly and Oscar, she took over her husband’s contract and duties at National Parks, including week-long excursions into the forest. She worked in Churumbelos Range National Park for a year and a half, until she resigned when she was asked to go on a tour near where her husband stepped on the mine. “What will become of my children if something happens to me? I thought. National Parks is an excellent employer and its objectives are praiseworthy, but the risk is always there,” she recalls.

“What will become of my children if something happens to me? I thought. National Parks is an excellent employer and its objectives are praiseworthy, but the risk is always there”

Yadira Vargas

Julia Miranda acknowledges these problems with insurance companies, which is why National Parks is currently working on a proposal to modify work regimes for park rangers in dangerous areas, providing them with risk bonuses and additional protective measures. The proposal, she explained, is ready but requires legal passage in Congress.

The Duarte family suffered another big disappointment when they wrote to the rector of the National University of Distance Education where Martín studied, asking them to consider granting him a posthumous degree.

They received a cold ‘no’ as an answer. According to Javier, “The answer was that it’s not possible, that Martín had to finish his ninth semester, when it was a question of human dignity.” They did not care that this harmless favor was exactly that which could help them rebuild their lives.

Elsa later said, “Imagine, the satisfaction of seeing our son as a psychologist.”

Disappointed by the State, the Duarte family decided not to seek legal recognition under the Victims Law passed by Juan Manuel Santos’s government in 2011 identify and redress the 8.8 million victims of the Colombian conflict. Therefore, they are not counted in the statistics detailing the legacy of atrocities that half a century of violence left behind.

“It is an open wound we feel every day. We mainly want Martín to be remembered”

José Venancio Duarte

Although the victims’ registrar closed in 2015, some legal experts believe that an extraordinary two-year extension for reasons of force majeure should apply to victims of the FARC, given that many live in regions where there were no conditions to denounce what happened to them. That period, which would have begun with the end of FARC’s disarmament in August 2017, will end for the Duarte family in six months.

In the end, what do the families like those of Martín, Jairo, Jaime or the recently deceased Wilton seek?

“It is an open wound we feel every day. We mainly want Martín to be remembered,” said José Venancio Duarte.

“Heroes wear not only [military], green but also [park ranger] blue”.

Rodrigo Botero

For each family, the form this may take is different, but the background is the same: a plaque, the name of a rural school, their photo in a public building, a hall of fame showing -in Rodrigo Botero’s words- that “heroes wear not only [military], green but also [park ranger] blue.”

As Javier says, “Park rangers should be given the status that they have in other parts of the world: they are protectors of nature and communities, disseminators of life. But here, they are nobody.”