Various social leaders and activists who have questioned the potential risks and impact of using fracking in Colombia’s Middle Magdalena are denouncing death threats against them. As the country nears a decision on whether to embrace this technology to extract oil or not, local communities feel their personal safety is compromised each time they voice their concerns.

The death threat that one of the most representative community leaders of the town of El Llanito in Barrancabermeja received on his mobile phone brought back memories and fears of violence to the area’s 3,000 inhabitants, that they believed had been overcome. It happened in mid-April 2018, weeks after a meeting between the community and officials from the oil company Ecopetrol S.A.

The meeting took place in the community hall “Lucho Arango”, one of the most emblematic sites of this town.

As a National Center for Historical Memory report published in 2014 documented, Lucho Arango was a man who defended the interests of the fishermen of El Llanito throughout his lifetime, as well as those of the entire Middle Magdalena region in northwestern Colombia, in light of the effects that building works such as the construction of the Hidrosogamoso Hydroelectric Plant are having on the area. This report also states that on February 12, 2009, hitmen belonging to the criminal group known as ‘Los Rastrojos’ assassinated him in the La Victoria neighborhood of the largest oil port in the country. Since then, his face and his name, drawn in bright colors, adorn the house.

“And what did that leave us? Nothing. We live in front of a marsh, from which Ecopetrol is nourished, but the town has no aqueduct with drinking water. We do not have roads, we do not have health posts”.

At the beginning of April, officials shared information with the community about the project dubbed “Guane A exploratory drilling area”, which was the result of an agreement signed between the government’s National Hydrocarbons Agency (ANH) and the largest state-owned oil giant, to explore and exploit conventional and unconventional reserves in an area of 5,700 hectares, divided between El Llanito and the neighboring municipality of Puerto Wilches. A request for an area of 7.5 hectares for five water catchment sites, which would be required for oil exploitation, was also added to this polygon.

That day, the community’s rejection of the extractive project was unanimous. Community leaders declared that there, in that town formed by 17 villages located on the shores of the San Silvestre Marsh, a wetland that Colombia is considering protecting under the Convention on Wetlands of International Importance, known as the Ramsar International Convention, oil has been being extracted for more than 30 years.

“Now, with this proposal to begin fracking, which I understand requires huge amounts of water, they will leave us without a marsh”

“And what did that leave us? Nothing. We live in front of a marsh, from which Ecopetrol is nourished, but the town has no aqueduct with drinking water. We do not have roads, we do not have health posts,” says the leader who, following the threats received, asked to omit his name.

“This was a fishing community, fish was plentiful. Now go and try to get a fish to see if you can! Since they began to exploit oil, the marsh is finished,” recalls the same leader who, despite his delicate situation, continues to lead the community’s opposition to the oil project. “Now, with this proposal to begin fracking, which I understand requires huge amounts of water, they will leave us without a marsh. Those of us at that meeting rejected the proposal, threatened to march, carry out strikes and even resort to legal means to avoid fracking. And what do you think about the fact that fifteen days later they called me to threaten me with death?”

A repeated history

El Llanito is not the only town where opposing fracking leads to threats and accusations.

Some 150 kilometers north of Barrancabermeja is San Martín, a town with close to 17,000 inhabitants in the neighboring department of Cesar. In April 2016, fifty citizens with very different profiles came together to create the Water, Territory and Ecosystems Defender Corporation (Cordatec), whose fundamental purpose is to reject the implementation of fracking pilot tests in San Martín land.

Although oil activity in San Martín goes back to the 70s, when the company Petróleos del Norte started operations in the Mono Araña and Tisquirama wells, the town only saw modest volumes of crude oil. In the last two decades, the daily production has not exceeded between 300 and 1,400 barrels of oil, according to figures from the National Hydrocarbons Agency (ANH).

the town only saw modest volumes of crude oil

However, studies conducted by Ecopetrol in 2011 show that in the so-called Mid Magdalena Valley, where San Martín is located, geological, geophysical and reservoir engineering analyses estimate that there is a potential of between 2,400 million and 7,400 million barrels of technically recoverable oil and gas.

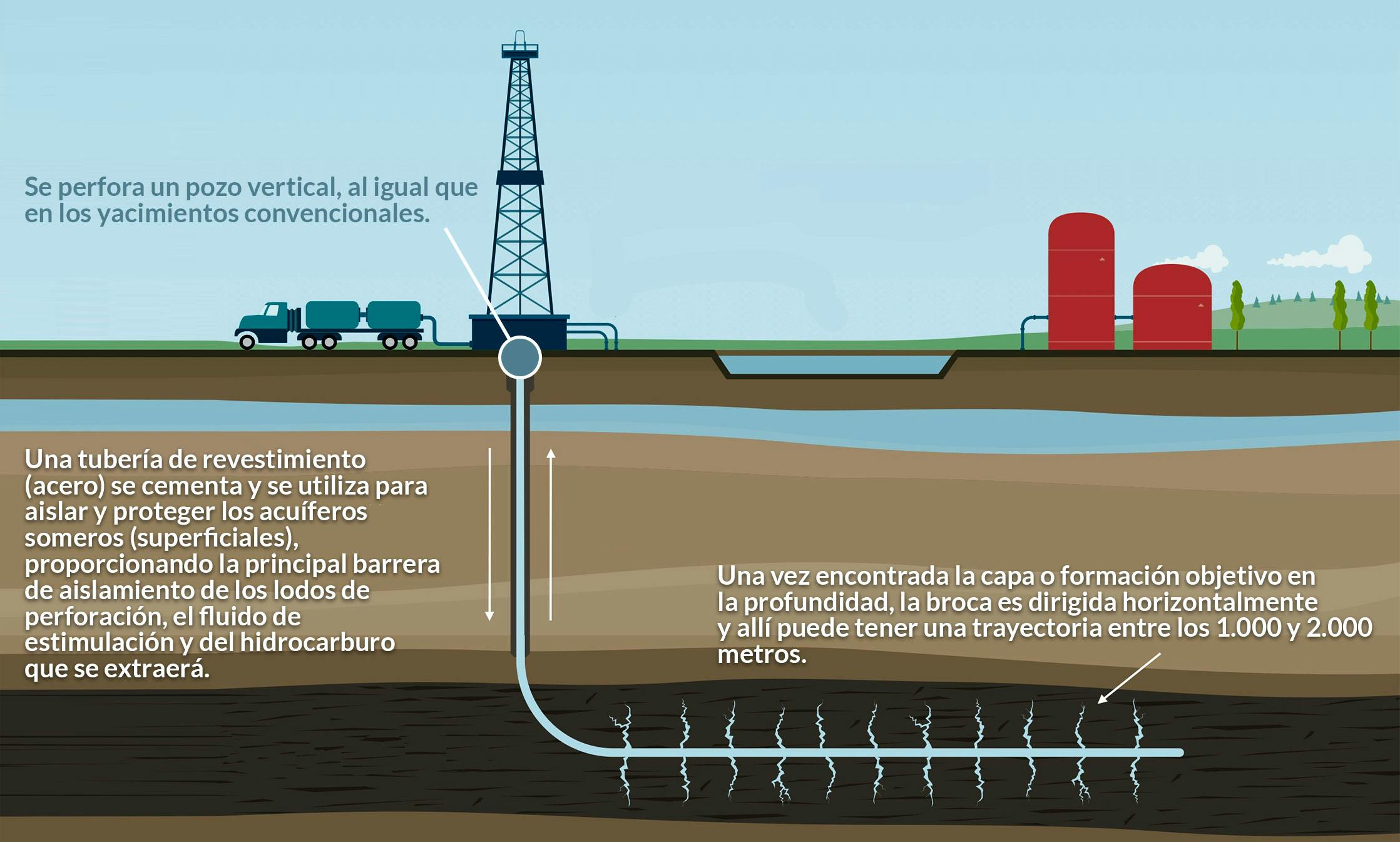

The problem is that these hydrocarbons are still in what is known as source rock. That is to say, low in a geological formation with little permeability that stores crude oil and gas at depths greater than 3,000 to 4,000 thousand meters. For this reason, these type of reserves are called “unconventional” and their exploitation is only possible through a technology called ‘fracking’.

although hydraulic fracturing had been carried out since the 1950s, fracking was only possible when highly specialized machinery was invented

This technology, which began to be used in the United States in 1999, has hydraulic fracturing as its starting point, which involves the injection, at very high pressure, of huge quantities of water mixed with sand and chemicals, which generates microcracks in the source rock to allow crude oil – or gas – to rise to the surface.

As explained by Óscar Vanegas, professor of energy geopolitics at the Autonomous University of Bucaramanga, although hydraulic fracturing had been carried out since the 1950s, fracking was only possible when highly specialized machinery was invented, such as “Top Drive” drills called ‘bottom engines’, which allowed the rock to be drilled horizontally and not vertically, which was the way that the oil industry had been working for a century.

“And, as far as we understand, fracking could generate serious environmental problems in our municipality, such as the contamination of groundwater sources and bodies of water such as rivers, streams and marshes, as well as an increase in seismic events,” notes Dora Stella Gutiérrez, current president of Cordatec. Therefore, Dora Stella adds, from the moment of its creation, the environmental organization has held workshops, forums, seminars, marches and awareness days against this technique. And this has cost them accusations, stigmatization, death threats and attacks on their lives.

“fracking could generate serious environmental problems in our municipality, such as the contamination of groundwater sources and bodies of water”

Dora Stella Gutiérrez

The most recent attack against a member of Cordatec happened on January 23. That day, at 1:00 in the afternoon, a man repeatedly shot at José Orlando Reina, a well-known activist in the municipality, when he was walking through the streets of the center area of his town, near the police station. The shots caused the reaction of several uniformed officers, who, in an exchange of fire, killed the hitman. The leader was helped and sent to the hospital in the nearby municipality of Aguachica, where numerous surgical interventions saved his life.

The attack against Reina is added to a long series of aggressions that, until now, have not left fatalities.

“The truth is that the situation is complex”

Dora Stella Gutiérrez

In September 2017, another of its leaders, Jassiel Leal, an environmental engineering student, received a couple of phone calls in which, in a threatening tone, he was ordered “not to continue defending what is not in his interest”.

Two months earlier, on July 20, armed men broke into the house of Crisóstomo Mancilla, another member of Cordatec and president of the community board of El Loro, and shot him several times. Wounded, Mancilla managed to be transferred to a health center where they saved his life.

Two months before that, on May 29, two other members of Cordatec, Marina Medina and Jorge Eliécer Torres, who also serve as presidents of community boards in two important neighborhoods of San Martín, received threats because of their negative positions towards fracking.

“We had been carrying out some workshops with the community, explaining what fracking is and why it is so harmful to our territory, but we have not been able to start this year, because the situation is as tense as it is”.

Dora Stella Gutiérrez

In addition to the aforementioned incidents, a pamphlet was circulated in February 2017, signed by the so-called Gaitanista Self-Defense Forces of Colombia, an armed structure that emerged in 2008 after the demobilization of the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC), in which they threatened death to “leftists, human rights activists, environmental leaders and indigenous leaders.”

“The truth is that the situation is complex”, acknowledges the president of Cordatec. “Since the middle of last year, the UNP (National Protection Unit) gave us a collective scheme [of protection], consisting of an armored car and two bodyguards, so that members of the corporation can mobilize. But the truth is that it is not easy. We had been carrying out some workshops with the community, explaining what fracking is and why it is so harmful to our territory, but we have not been able to start this year, because the situation is as tense as it is.”

To frack or not to frack

The discussion about exploiting unconventional reserves through fracking is not new in Colombia.

Since the beginning of the current decade, the national oil industry has been raising the issue of the need to resort to this technology – which provokes strong resistance among the environmental and political sectors – to significantly increase oil and gas production and, thus, guarantee the country’s self-sufficiency in terms of energy.

In light of the decrease in current oil reserves, the debate has recently become more urgent and of higher priority.

In light of the decrease in current oil reserves, the debate has recently become more urgent and of higher priority. In fact, it featured in the last election campaign of the Presidency of the Republic: in Bucaramanga, on April 11, 2018, current President Iván Duque committed himself to not allowing the implementation of this technique, if he triumphed in the presidential elections.

“We have diverse and complex ecosystems, underground aquifers of enormous wealth and risks of increased seismicity due to the types of soils we have. That is why I have said that in Colombia there will be no fracking”, the now-President Duque said at the time, before a group of academics and university students gathered in the auditorium of the Autonomous University of Bucaramanga.

Last November, three months after assuming the Presidency, Duque convened an Interdisciplinary Commission of Experts in order to study the possible consequences that the application of the technique of fracking would cause in the country.

“We have diverse and complex ecosystems, underground aquifers of enormous wealth and risks of increased seismicity due to the types of soils we have. That is why I have said that in Colombia there will be no fracking”

Iván Duque

The mission of this commission, comprising thirteen academics from diverse disciplines from biology to law, philosophy, economics, engineering – civil, mechanical and of oil – to the resolution of intercultural conflicts, was to discuss the feasibility of fracking in the country, after talking with communities in the territories where pilots are proposed, evaluating the impacts of this technology in other countries and reviewing the existing environmental regulations.

Its final report, which the experts delivered to the national government on March 15, did not give free rein to fracking in Colombia, but determined that it is possible to carry out comprehensive pilot projects that allow deepening knowledge about the technique, as well as assessing its true effects.

The document, perhaps due to the heterogeneity of the Commission’s members, reached apparently contradictory conclusions, such as highlighting the enormous economic potential of the country’s unconventional reserves, whilst, at the same time, warning about the limited access that communities have to information about the projects and the lack of sufficient studies on groundwater, risks of seismicity, the possible contamination of ecosystems, and the capacity of the institutions responsible for environmental control.

“What the Commission said is that Colombia has the necessary regulations to develop this technique”

Francisco José Lloreda.

The commission also made a series of recommendations to the Duque government, including disclosing all of the information about the projects to the communities; identifying gaps in information on ecosystems, hydrogeology and seismicity; agreeing mechanisms for citizen participation and oversight; building social baselines; agreeing to manage health risks with residents close to pilot projects; and identifying the shortcomings of the institutions responsible for environmental control.

The oil industry interpreted the conclusions of the Commission as a responsible call for the national government to implement the technique in Colombia and as a rebuttal of the arguments of those who oppose fracking.

“The country has oil and gas reserves that would last six and eleven years respectively”.

Francisco José Lloreda.

“What the Commission said is that Colombia has the necessary regulations to develop this technique. In fact, they are the most rigorous and demanding at international level. And that the possible environmental impacts that can result from this technique are fully identifiable and can be prevented,” says Francisco José Lloreda, president of the Colombian Petroleum Association (ACP), which brings together oil companies.

“The country has oil and gas reserves that would last six and eleven years respectively. These are extremely short times for this industry, (so) it is essential to maintain energy self-sufficiency. It is also essential that the country has surplus oil to export, with regards internal finances”, adds Lloreda, who was a Minister of Education in the 1990s.

Is there enough ‘black gold’?

The economic importance of fracking is clear. So much so that, according to Lloreda, 15 percent of oil and 30 percent of gas worldwide, are exploited through this technology.

That boom, however, is divisive in many countries. France, Germany and Ireland have banned the technique, while some states of Australia and the United States have put a moratorium on fracking.

In Colombia, according to Ecopetrol, there are unconventional reserves in Catatumbo, Norte de Santander, Putumayo and Caquetá, although the greatest potential lies precisely in the geological formations known as La Luna and El Tablazo in the Middle Magdalena Valley and Cesar, precisely fears have been aroused among the local population.

France, Germany and Ireland have banned the technique, while some states of Australia and the United States have put a moratorium on fracking.

It is also there where two international companies already have contract award resolutions from the National Hydrocarbons Agency (ANH) to start pilots.

One of them is Parex Resources Colombia Ltd, a multinational company with its headquarters in Barbados, to which the ANH awarded an area of 61,679 hectares in the municipality of Cimitarra, Santander in 2014. Another is ConocoPhillips Colombia Ventura Ltd., based in the Cayman Islands, which, in 2015, obtained an “additional exploration and production contract for unconventional hydrocarbon reserves” to the one that it has had since 2009 in San Martín, Cesar.

“significant benefits would be generated in terms of job creation and the demand for goods and services in the areas where the activity would take place”

“Production in Middle Magdalena could increase by at least 250,000 barrels per day. Furthermore, significant benefits would be generated in terms of job creation and the demand for goods and services in the areas where the activity would take place,” an Ecopetrol spokesperson told us.

Although there are no estimates about to what extent fracking could benefit the country’s finances, Ecopetrol emphasizes that, in 2018 alone, it transferred 23.1 trillion pesos in dividends (8.2 billion pesos), taxes (8, 8 trillion pesos) and royalties (6.1 trillion pesos) to the nation. In addition, it points out that, that same year, it contracted goods and services to more than six thousand companies in the territories where it developed its operation, for 10.4 billion pesos, and generated 34,805 indirect jobs.

Ecopetrol S.A has proposed the execution of controlled fracking pilots, with oversight from the communities, territorial entities and regulatory authorities

Hence the companies’ expectation is that the national government gives the green light to the fracking pilots. “Over the past two years, Ecopetrol S.A has proposed the execution of controlled fracking pilots, with oversight from the communities, territorial entities and regulatory authorities, to be able to apply the technology and know, through this field trial, what are their real effects”, explained its spokesperson.

Environmental and social risks

Unfortunately, in those areas where these pilot fracking tests were to be carried out, violence has been directed at environmental leaders who are concerned about the technique.

This was documented by the Early Warning System (SAT) of the Ombudsman’s Office, the state entity that monitors the risks of human rights violations throughout the country.

“The social and community leaders who in recent months have been subjected to threats, harassment and attacks in the department of Cesar belong to social organizations, especially rural or peasant organizations, who work on (among others) the following activities: 1) defense of the territory; 2) opposition to the extractive development model as well as environmental damage caused to ecosystems as a consequence of the expansion of mining and agro-industry,” it says in a risk report dated November 28, 2018.

in those areas where these pilot fracking tests were to be carried out, violence has been directed at environmental leaders who are concerned about the technique

The current situation suffered by members of Cordatec, San Martín’s environmental organization, is one of the most worrying to the SAT of the Ombudsman.

“Several dignitaries of the Defender of Water, Territory and Ecosystems Corporation –Cordatec – have been the subject of repeated threats, due to the days of peaceful resistance that took place for several days from September 7, 2016, against the use of the hydraulic fracturing technique known as fracking, for the extraction of oil made in Cuatro Bocas, a jurisdiction of San Martín”, says the same report.

A similar warning was made by the Ombudsman’s Office about Barrancabermeja, considered the oil capital of Colombia, being the location of the country’s main refinery.

In an early warning dated November 2018, the Ombudsman’s Office asserted that the development of new oil exploration and production projects coincided with the increase in threats against environmental leaders, community leaders and human rights defenders in the municipalities of the Middle Magdalena region in Santander. An example of the above, indicated the Ombudsman’s Office, were the threats made against leaders of the towns of Ciénaga de Opón, La Fortuna and El Llanito in Barrancabermeja.

“Illegal armed groups, including the so-called ‘Gaitanista Self-Defense Forces of Colombia’, have deployed practices of harassment, intimidation, and the cooptation of community leaders that establish direct dialogue with the contractors of Ecopetrol”

All of them have in common the fact that they live in areas where conventional and non-conventional reserve exploitation projects are taking shape. The SAT of the Ombudsman’s Office argues that this increase in intimidation could be related to the interest of criminal groups present in the region, to obtain resources through the cooptation of contracts for goods, personnel and services required by oil companies for the development of their work.

“Illegal armed groups, including the so-called ‘Gaitanista Self-Defense Forces of Colombia’, have deployed practices of harassment, intimidation, and the cooptation of community leaders that establish direct dialogue with the contractors of Ecopetrol. This is because it is between the relations for the supply of personnel and economic financing for the criminal structure through the contracts of goods and services required by these companies for the execution of their works”, concludes the Ombudsman’s Office in its Early Warning 076- 18.

In particular, the public body drew attention to the situation of Oscar Sampayo and Óscar Yesid Blanco, two well-known individuals from Barrancabermeja who, due to different circumstances, ended up setting themselves up as the fiercest opponents of fracking and standard-bearers of the protection of the environment and water.

The doctor and the political scientist

The problems for the two Oscars – one, a political scientist, and the other, a pediatrician – began in 2015.

At the end of that year, both Sampayo and Blanco reported that the water consumed by the people of Barrancabermeja was not suitable for human consumption, because the San Silvestre Marsh, the wetland that supplies the city’s aqueduct and 190,000 inhabitants, registered alarming increases in heavy metals, including mercury.

the water consumed by the people of Barrancabermeja was not suitable for human consumption, because the San Silvestre Marsh registered alarming increases in heavy metals

“There was a year in which I diagnosed 18 children with a very rare disease that consists of an immunological alteration. I started to look at what could be happening and, with the help of other colleagues, we saw that there was a direct relationship with exposure to heavy metals, including mercury“, recalls Blanco, an individual well respected by people in Barrancabermeja for his charisma, his vocation of service and his commitment to environmental causes.

“At that time, a trade unionist friend from Aguas de Barrancabermeja – the company in charge of the local aqueduct – gave me a report that the company had saved, written by the Bolivariana University, which indicated an increase of up to 25 percent in heavy metals, including mercury, in the marsh“, adds the doctor.

“The landfill was placed in the heart of an area that is considered an environmental reserve, with all the irregularities that you want”.

Óscar Sampayo

Thus began a row between environmentalists, the aqueduct company and the local mayor, Darío Echeverri. The disagreement intensified when Sampayo and Blanco pointed out that the deterioration of the marsh’s water quality was due to the construction of the Yerbabuena landfill in the neighborhood of Patio Bonito, in the heart of the District of the Integrated Management of Natural Resources of San Silvestre Marsh.

“The landfill was placed in the heart of an area that is considered an environmental reserve, with all the irregularities that you want,” says Sampayo, who set aside his work as a real estate entrepreneur to devote himself, in full, to the defense and protection of the environment. According to Sampayo, “the Oxy oil company donated the land where the works were done and that place would coincide with one of the blocks that Ecopetrol wants to exploit using fracking.”

“They degraded a territory that was an environmental reserve,” Sampayo continues, “because it is being degraded on account of the leachates that are spilling over the marsh, so that the environmental authority will then say: ‘Well, there’s nothing to protect, you can carry out fracking.’

Among the evidence that Sampayo presents is that, in 2013, the Autonomous Regional Corporation of Santander (CAS) – the regional environmental authority – approved “the theft of an area of the Regional District of Integrated Management of the San Silvestre Wetland for the construction and operation of a final disposal site for solid waste.”

“They degraded a territory that was an environmental reserve, because it is being degraded on account of the leachates that are spilling over the marsh, so that the environmental authority will then say: ‘Well, there’s nothing to protect, you can carry out fracking'”

Óscar Sampayo

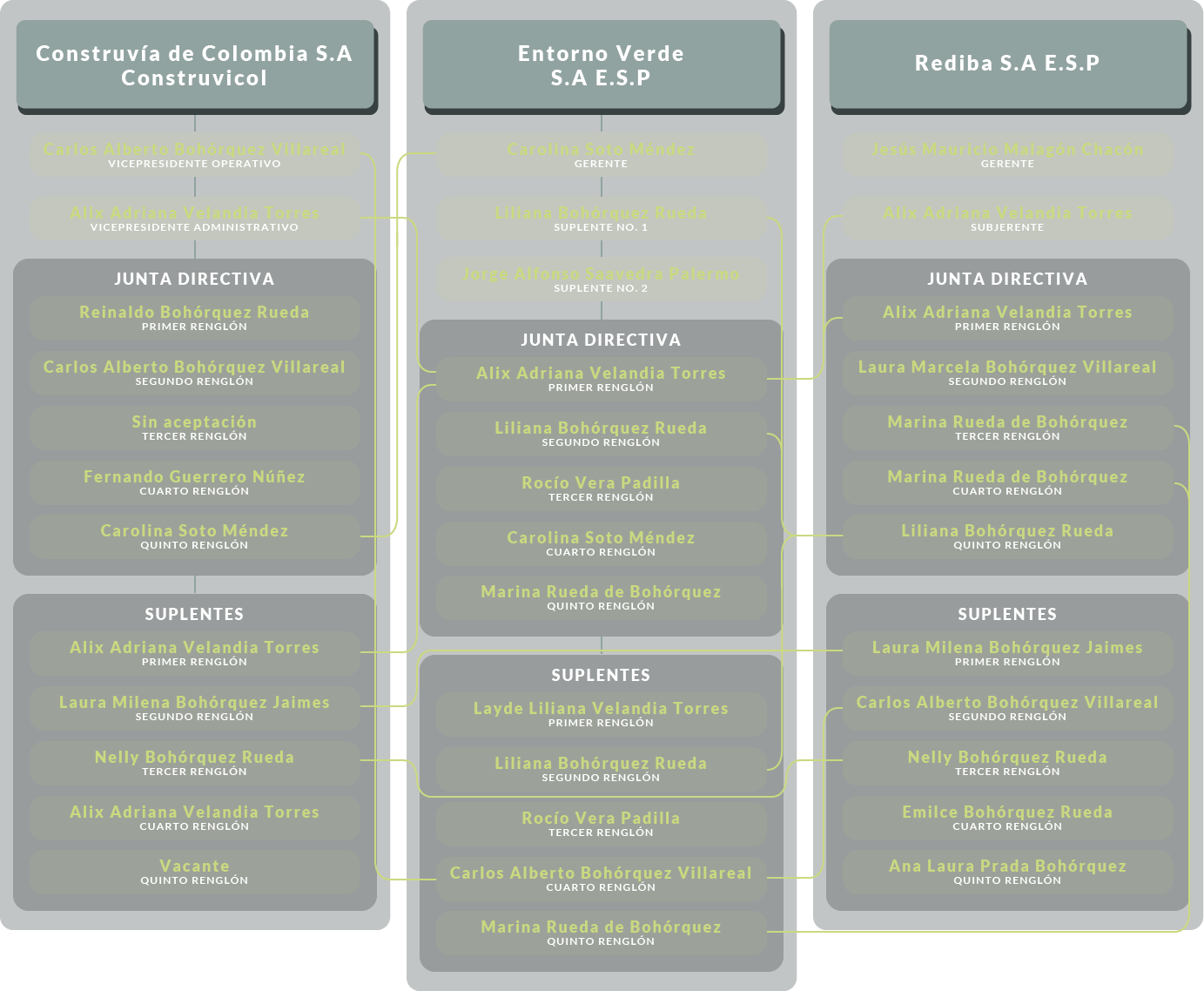

That approval was given after the company Entorno Verde S.A E.S.P. conducted a technical study that showed the feasibility of the work, which was awarded in 2014 to the construction company Construvías de Colombia S.A. (Construvicol) and that came into operation in 2015 with the labor of Rediba S.A. E.S.P.

The complaints of the environmentalists reached the ears of the Office of the Attorney General of the Nation. As part of an anti-corruption day that took place in Barrancabermeja on June 13, 2017, the Office of the Attorney General collected evidence and testimonies from residents of the neighborhood of Patio Bonito, which, two months later, allowed him to order the arrest of the then manager of Rediba, Liliana Forero, accused of the crimes of procedural fraud, damage to aggravated natural resources, damage to natural resources in homogeneous with environmental contamination, concealment and destruction of probative material and invasion of property. On September 22 of the same year, a judge from Barrancabermeja ordered her imprisonment.

This company, together with Construvicol and Entorno Verde, is connected to Reinaldo Bohórquez, a powerful contractor who has executed infrastructure works in several municipalities of Santander and manages the garbage business in Barrancabermeja, Floridablanca and Girón and the final disposal of waste generated by oil exploitation. His company Construvicol will be responsible, in partnership with the Spanish company Aqualia Intech, for the construction of the Solid Waste Treatment Plant (PTP) of Barrancabermeja.

In political circles in Santander, he is recognized for financing political campaigns, including Darío Echeverri, who was elected in the last elections for Mayor in Barrancabermeja. “I participated in his campaign because he said he would not allow the landfill. In fact, when the Mayor wins, I am appointed Liaison Officer for the Mayor’s Office with the CAS,” says Sampayo, who adds that, “after six months the man changes his position, they dismiss me and give him free rein over the landfill. Publicly it was said that it had been financed by Bohórquez.”

This led to a recall process led by several citizens of Barrancabermeja, including the pediatrician and Óscar Sampayo. Echeverri managed to maintain his mandate at the polls, but, in February 2018, the Attorney General’s Office arrested him for the crimes of constraint to the voter, obstruction of the electoral contest, embezzlement and conspiracy to commit a crime. According to the Attorney General’s Office, Echeverri resorted to corrupt practices to prevent voters from turning out in masse on the day organized for the recall.

“What has that cost us? Well, in my case, being victim of the biggest smear campaign by the lawyers of Bohórquez’s companies”

Óscar Yesid Blanco.

It has not been the only fight that Sampayo and Blanco have had against Bohorquez’s lawyers. In a humorous tone, both assure that they have had to attend the judicial courts so many times in the last years that both of them lost count.

“We report the presence of leachates in the water of Barrancabermeja due to the operation of the landfill. We also note that the environmental authorities have turned a blind eye so as not to take any kind of action against this man. What has that cost us? Well, in my case, being victim of the biggest smear campaign by the lawyers of Bohórquez’s companies,” says the doctor Óscar Yesid Blanco.

According to Blanco, a local journalist posted a false news article about him on his website. After the doctor reported him for slander, the journalist acknowledged before the judge that he had received a payment from one of the lawyers for Rediba S.A.’s. E.S.P, one of Bohórquez’s companies.

“It turns out that a journalist, Gustavo Duarte, published on his website, La Tea Noticia, a false news article about me,” continues the pediatrician. “I reported him for slander. Before the judge, the journalist acknowledged that the lawyer, Cristián Gutiérrez, who we later learned worked for Rediba S.A. E.S.P, Bohórquez’s company, paid him to publish lies about me. That process was carried out by the Prosecutor’s Office in Barrancabermeja.”

“They told me: ‘Doctor, we have very serious information, from very reliable sources, that there is a plan in place to make an attempt against your life. We suggest you leave the city.’ I did not think twice and the next day, I was out of the country”

Óscar Yesid Blanco.

The pressures against both environmentalists intensified as the severity of their complaints increased. In October 2018, Sampayo managed to become part of a protection scheme of the National Government Protection Unit. The doctor, who did not have the same luck, received a call in November from the Regional Corporation for the Defense of Human Rights (Credhos), a regional NGO on human rights issues.

“They told me: ‘Doctor, we have very serious information, from very reliable sources, that there is a plan in place to make an attempt against your life. We suggest you leave the city.’ I did not think twice and the next day, I was out of the country,” he says from his exile in a city he prefers not to name.

Expectantly

Despite the threats, almost all leaders against fracking maintain that they will continue to oppose the technique.

In El Llanito de Barrancabermeja, they do not rule out conducting protests, civic strikes and marches, to protect the San Silvestre Marsh, which they consider the life and soul of its town.

Despite the threats, almost all leaders against fracking maintain that they will continue to oppose the technique.

In San Martín, they continue with their resistance towards the pilot tests. In fact, following several meetings and public hearings held throughout 2018, members of Cordatec and officials of the National Agency of Environmental Licenses (ANLA), the entity decided to suspend temporarily two environmental licenses granted to the oil company ConocoPhillips Colombia Ventura Ltda, through Autos 6117 of October 9, 2018 and 6445 of October 23 of the same year.

According to the government entity that oversees environmental licenses, the environmental impact studies – in their words – “do not meet the requirements of the environmental authority” because “they do not comply with the terms of reference for the exploitation of hydrocarbons in unconventional reserves.”

“he company continues to bring machinery into the town, along (path) Cuatro Bocas, where the well Pico Plata 1 is. And truthfully, we do not know what they are doing there.”.

Dora Stella Gutiérrez

“That was like a small achievement for us,” says Dora Stella Gutiérrez, current President of Cordatec, “but still, it’s a temporary suspension. The company continues to bring machinery into the town, along (path) Cuatro Bocas, where the well Pico Plata 1 is. And truthfully, we do not know what they are doing there.”

For environmentalists, the discussion about fracking should not be limited solely to the economic potential of the subsoil, but to the natural richness of its surface.

“it is time to think about making the transition to clean, renewable energies”.

Óscar Sampayo

“If the oil runs out, does life end in Barrancabermeja? I think not and I think it is time to think about making the transition to clean, renewable energies,” contends Sampayo.

Meanwhile, Dora Stella, who forged a prosperous career as a grocery retailer in San Martín, asserts that oil will not be the economic salvation of her town.

“With fracking, it will be worse, they will use up the water and the earth and we will then have to go to another town because there will be no life here”

Dora Stella Gutiérrez

“Hace como tres años llegó esta empresa petrolera al pueblo con sus trabajadores y contratistas ¿Subieron nuestras ventas desde entonces? No. Por el contrario, ya tenemos problemas de prostitución y robos. Con el fracking será peor, acabarán con el agua y con la tierra y nos tocará entonces irnos para otro pueblo porque aquí ya no habrá vida”, dice Dora Stella.

“About three years ago, this oil company arrived in town with its workers and contractors. Have our sales increased since then? No. On the contrary, we now have problems of prostitution and robberies. With fracking, it will be worse, they will use up the water and the earth and we will then have to go to another town because there will be no life here,” says Dora Stella.